1. Tarantino's stories are surprisingly logical

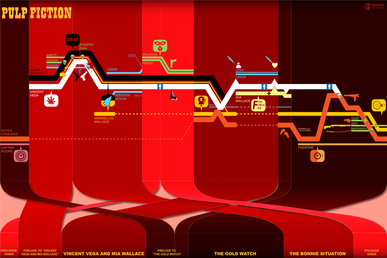

A Pulp Fiction timeline by Shahed Syed

A Pulp Fiction timeline by Shahed Syed Pulp Fiction makes this clearest of all, presenting three interwoven plot lines with quietly similar structures. Each narrative establishes a conventional conflict, only to complicate matters with a late, unforeseen interruption that changes the stakes entirely. Butch (Bruce Willis) must recover a precious watch and flee town before Masellus (Ving Rhames) whacks him. Vincent (John Travolta) must entertain Mia (Uma Thurman) without entertaining his own sex drive. Vincent and Jules (Samuel L. Jackson) must clean up a bloody car before their buddy's wife gets home. Butch nabs the watch, Vincent proves a gentlemen, and both Vincent and Jules save the missus from undue heartache. Yet Butch soon runs straight into Marcellus, Mia passes out from drug overdose, and the Vincent/Jules duo get held up while trying to decompress at a diner. Tarantino routinely raises the tension by giving his characters (and the viewing audience) a bit of false comfort before forcing them to confront an even stickier situation than before.

| What's more, the characters arguably get what they deserve. Butch's careless arrogance eventually leaves him bound and gagged. It's only once he turns back to rescue his enemy that his fortunes change for the better. Vincent's conscientiousness saves Mia, but his stubborn refusal to walk away from crime ultimately gets him killed. | Tarantino's stories may be laced with profanity and rife with broken bones, but they're told with the narrative stability of a Pixar short. |

2. Tarantino writes better chapters than books

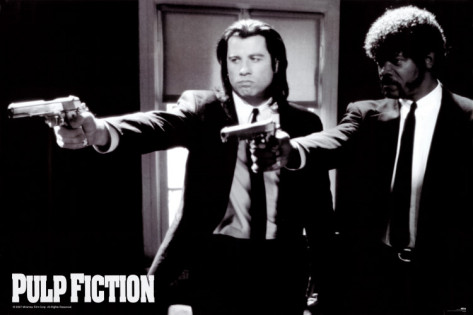

Samuel L. Jackson in Pulp Fiction

Samuel L. Jackson in Pulp Fiction Taken together, however, the chapters can overwhelm viewers' emotions to the detriment of the film as a whole. It's like the time you surprised your high school crush with concert tickets, chocolates, love poetry and a dozen roses. Just because the buttercreams were tasty doesn't mean they belonged on the date.

| Django in particular packed a little too much Taranfoolery in its sprawling 180 minutes. Yes, the final half hour was splendidly cathartic. It was also shamefully indulgent. Alas, Tarantino couldn't help himself. | Just because the buttercreams were tasty doesn't mean they belonged on the date. |

3. Tarantino employs a stand-up comic's sense of humor

The Klan in Django Unchained

The Klan in Django Unchained | Stand-up comics think differently. In a way, they blend the two styles, taking day-to-day "banana peel" situations, and crafting witty, Gilmore Girl observations about them. Onstage, this hybrid style is a necessity, as only the combination of shared experience and uniquely amusing commentary will win over a skeptical, half-drunk crowd. The silver screen—with its gorgeous stars and special effects—can gloss over a few bad jokes; but a brick wall, microphone, and 40-year-old divorced guy? Good luck. | The silver screen—with its gorgeous stars and special effects—can gloss over a few bad jokes; but a brick wall, microphone, and 40-year-old divorced guy? Good luck. |

4. Tarantino is master of the payoff

The Gold Watch in Pulp Fiction

The Gold Watch in Pulp Fiction | You could make the case that Tarantino's setups are too blatant. Film snobs might point to Citizen Kane, with its "Rose Bud" payoff so subtle it might take two full viewings to grasp it. In my mind, however, Tarantino needs to be obvious. He directs with such a wacky, busy mentality that his approach to setup/payoff brings crucial organization to his otherwise frantic films. | He's like F. Scott Fitzgerald when it comes to symbols or Keanu Reeves when it comes to underacting. |

5. Tarantino's excess works better on the page than on the screen

'The Wolf' in Pulp Fiction

'The Wolf' in Pulp Fiction After watching Pulp Fiction, I believe I've isolated the problem. Tarantino's unrestrained writing works wonderfully; his unencumbered visual composition—with all the blood, guts and gore—probably goes a burst artery too far. Pulp Fiction's Winston 'The Wolf' Wolfe (Harvey Keitel) displays Tarantino's exaggerated style at its best. Unimaginably suave and caricatured to the extreme, his entire involvement in 'The Bonnie Situation' drips with Tarantonian indulgence. The character surprises—even shocks—but only because he's so level-headed and unflustered. It's the rare Tarantino surprise devoid of unexpected violence.

| Give Tarantino a camera crew and a samurai sword, however, and he'll quickly paint the studio red. It's not the plot points themselves that are problematic: it's the way the director lingers on unpleasantries just long enough to distract from the true cleverness of his stories. I'm happy to hear about the mass butchering of the Third Reich in Inglorious Basterds. I'd just rather listen to Brad Pitt's Lt. Raine chew over another page of Tarantino's witty dialogue than watch another three minutes of Nazis turned to swiss cheese. The Butch/Marcellus torture scene in Pulp Fiction may lead to a key point of resolution, but I'd prefer to marvel at the characters' changed relationship than attempt to forget the extended portrayal of sexual assault. | It's not the plot points themselves that are problematic: it's the way the director lingers on unpleasantries just long enough to distract from the true cleverness of his stories. |

I'll abide the pools of blood and titanic runtimes so long as Tarantino's films maintain the structure, humor, and narrative payoffs that made the man famous in the first place. He may seem inscrutable at a glance, but look a little harder and you'll find a capable writer and fearless director. Like Pulp Fiction itself, he makes a lot more sense once you go back to see what happened first.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed