If only the same could be said of the plot. Russell may be master of mood, but the film’s final ten minutes play out with a surprisingly bland neatness. It’s a little like a rollicking holiday party that gets a (cheerful but firm) visit from the sheriff. We know you’re having fun, but you need to keep it down. After throwing a hell of a party, American Hustle grabs one last drink, nods politely to its guests, and shuffles them out the door.

It’s tough to say whether this sort of pat conclusion is turning into Russell’s signature or failing (or, perhaps, signature failing). Famously, Silver Linings Playbook spun from hopeless to Hollywood in its final five minutes, its two principal characters learning a series of valuable lessons all at once, and at just the perfect time. Russell’s critics will continue to lament his fairy tale sensibilities, while apologists will point to a defiant optimism—a modern-day director willing and able to find goodness in flawed, human characters. In my mind, Russell’s happy endings are to be celebrated; he just needs to find ways to earn them, rather than spring them on viewers when he discovers it’s time to end his movie.

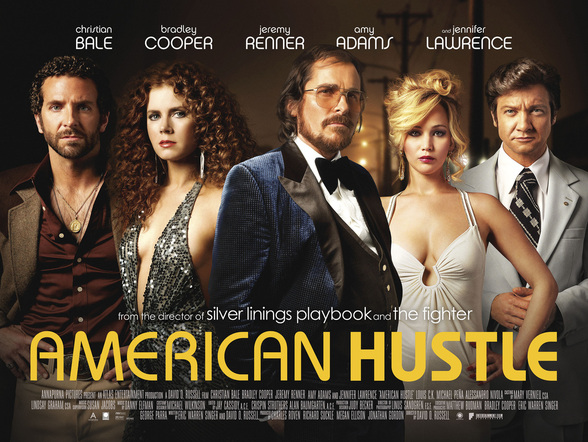

Happily, almost everything else about American Hustle is delightful. Irving Rosenfeld (Christian Bale) commands a soft, puzzling mystique, with a velvet-meets-gravel voice and a smile so honest you’ll believe him even when you know he’s lying. In an early scene, we see Rosenfeld lounging by a pool, his hairy beer-belly exposed to all the world, his eyes twitching to the beat of Duke Ellington’s sassy “Jeep's Blues.” After years of being Mr. Batman, it’s fun to see Bale play a role so far removed from the hard-boiled quips of a jaded super hero.

Opposite Irving, Sydney Prosser (Amy Adams) infects the film with a constant, playful energy. One moment, we settle in with Sydney as she plays with her on-again, off-again British accent, teasing Irving while they plan their next con. The next moment, American Hustle cascades through time, the characters dancing, then debating, the camera pulled as though by magnetism toward Sydney. It’s as if she’s towing us along with her, our sole point of consistency in a story rife with scheming and deceit. The film might actually overdo Adams’ cleavage (part of that ‘magnetism’ comes from some strategic wardrobe planning), but to Adams’ credit, her clever wordplay outshines her ostentatious figure.

Bradley Cooper performs admirably as the third con artist, playing the not-quite-competent FBI agent, Richie DiMaso. His sexual desire for Sydney is particularly intriguing, as DiMaso waffles from boyish curiosity to a darker, more violent longing. That said, his performance will likely fade next to the mysterious Bale and captivating Adams. Cooper has successfully acted his way out of the Comedy Zone, but there's still a dab of Orlando Bloom-genericness somewhere in his handsome, nervous face.

Meanwhile, Jeremy Renner and Jennifer Lawrence play supporting roles that deviate satisfyingly from each actor’s standard style. Renner’s Mayor Carmine Polito is disarmingly frank, a deeply caring politician attempting to navigate a profession filled with corruption. His practiced smiles and wavering resolve sneak up on you by the end of the film—it’s a nice pivot from the sharp-tongued action star we’ve come to know in films like The Avengers, Thor, and Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol. Meanwhile, Lawrence’s turn as a fussy housewife is a total riot, her outward cluelessness disguising a character much cleverer than anyone anticipates. Lawrence has proven she can carry a film, but American Hustle makes me want to see more splashes of Lawrence in saucy supporting roles. She has a knack for stealing scenes before handing them gracefully back to the stars.

In the end, American Hustle is a rousing success—not because it skewers society or reflects some kind of deep truth, but rather because it remembers how to engage, to entertain, and to entrance. Late in the film, we finally get to see all the principal actors together, the camera darting playfully around the room, the characters glaring at one another spitefully, the tension thick, the scheming nasty. A moment of heavy silence builds the suspense—two beats, three, four—then all at once it topples, with a clever line from a minor character and a bit of deft camerawork from Russell. Sometimes, pure filmmaking is all you need.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed