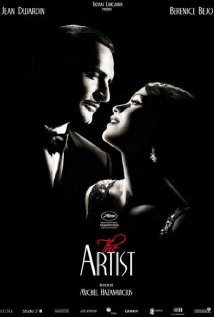

But The Arist's pure purpose and delightful leads eventually convinced me. Jean Dujardin plays George Valentin, the celebrated silent film actor unprepared for the advent of "talkies" (movies with sound). If you look closely, you can see Hollywood itself in the worried wrinkles of his beautiful face, watching nervously as TV, online media, and iPhone apps chip away at their towering industry. Dujardin accomplishes the tricky task of acting like he's acting, and his exaggerated smile (at first, a bit jarring), makes more and more sense as the film runs along. For a man who must maintain a public image, his too-perfect pearly whites thinly disguise a fear that he might lose everything.

Dujardin's co-star, Bérénice Bejo, plays Peppy Miller, a fine complement to the (quietly) crumbling George Valentin. Fresh, up-and-coming, and a little surreal, Peppy glides to stardom through a combination of cute looks, talent, and confidence. Her ascent to fame may be a bit overly glamorous and idealized, but it admirably captures how the public imagines celebrity success. We watch as George and Peppy flip roles: the star becomes the has-been; the wannabe, Hollywood's new darling. The film's very best scene, in which the two chat briefly on an M. C. Escher-inspired staircase, encapsulates their changing fortunes beautifully. Peppy stands a few steps above, ready to climb to never-before-seen greatness, while George—at the moment, just a couple steps below—knows he's doomed to descend into irrelevance. Escher himself would applaud.

Regrettably, The Artist's metaphors aren't always so subtly crafted. We see George (in a film within the film) sinking into a pit of quick sand, with frequent cuts to the real-life George and Peppy, watching from the audience. Oh no! His career is sinking! It might have worked in a short, passing clip, but the minute-plus sequence feels heavy-handed.

The Artist also overdoes it with George's adorable pup (played by "Uggie," a canine with a surprisingly storied youth). Hollywood seems to believe that a dog doing cute things—however obvious, predictable, or unrealistic—will only improve a film's chances with the public. Worse, Hollywood's probably right. To the doggie-ambivalent, however, Uggie's antics are tiresome. Late in the film, there's a moment of dog-heroism that would make Looney Toons proud. If only I'd seen it when I was 13.

Complaints aside, The Artist likely deserves its Oscar for Best Picture, and here I must admit fault with my previous (totally unwarranted) opinion. That said, had the film been released in 2012, I would have ranked it just below Silver Linings Playbook and just above Daniel Day-Lewis' presidential nose. And compared to other non-verbal cinema? The first ten minutes of Pixar's Up do silent exposition better than any ten-minute stretch in this film. In Up, watching Ellie cinch up tie after tie for Carl—as the fashion styles change and the chin hairs gray—displays a profound thoughtfulness and storytelling economy rarely found in The Artist. Pixar's opening montage transcended shtick; The Artist simply perfects the gimmick.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed