With The Great Gatsby (2013), director Baz Luhrmann tries so hard to craft a summer blockbuster that he sails straight past the soul of the 1925 F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. Perhaps he doesn't know any better. Or maybe he hopes the cruise will be so smooth we won't notice the shallowness of the waters below. Remarkably, it almost works.

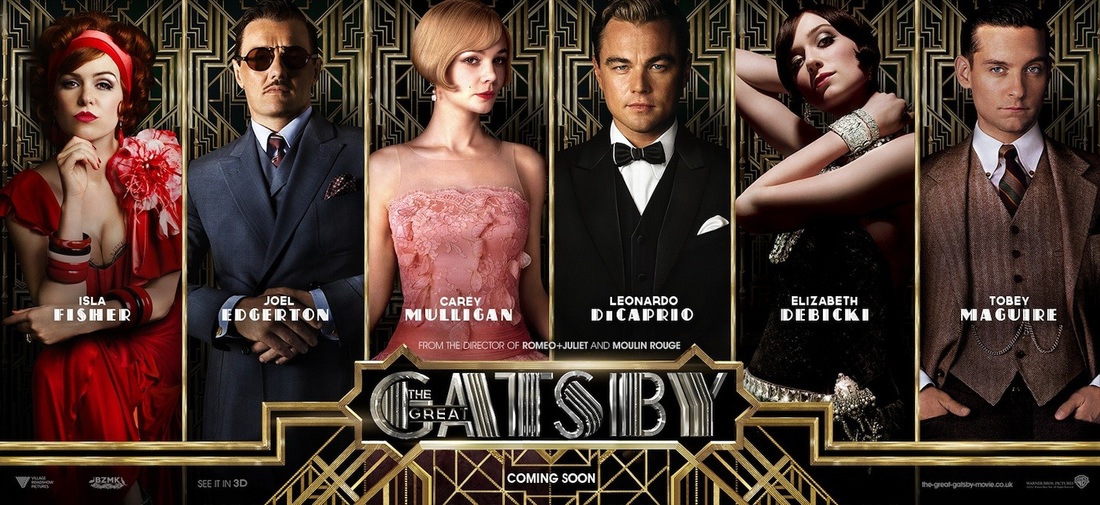

His biggest asset is Leonardo DiCaprio, who hasn't delivered a bad performance in 15 years. DiCaprio's Gatsby captures nearly every haunting note of the novel's title character, from his impossible hopefulness to his tightly masked fear of rejection. Through a series of dimple-perfect smiles, DiCaprio builds Gatsby's mystique to the point of legend, before the mirage disappears all at once in a brief, though fateful, burst of raw anger. To see DiCaprio's quivering, pleading Gatsby at the end of the film—as he tries, pathetically, to piece back together his shattered disguise—is near cinematic perfection.

It's just a shame Tobey Maguire's Nick Carraway keeps opening his mouth trying to explain everything. Eager, boyish, and a little overwhelmed in his role, Maguire maintains a dazed, just-happy-to-be-there smile throughout. If you look closely, you'll notice Tobey glancing off-camera for Luhrmann's proud approval after each successfully-delivered line. To be fair, Carraway is a thankless role on film. The performance would require a blend of deft charm and effortless detachment, and even then, would simply earn the actor a golf clap next to the dazzling Gatsby. Fitzgerald accomplished this balancing act through a series of nonchalant asides and nimbly interspersed commentary. Regrettably, there's nothing effortless, detached, nonchalant, or nimble about Maguire, who proves thoroughly miscast.

Still, Luhrmann's cinematic style—with rich color work; symmetrical set composition; and bold, deliberate cuts—creates a surreal spectacle (and suitable distraction) before Gatsby's big reveal. When we first meet Tom and Daisy Buchanan, we watch servants open and close their luxurious French doors with clocklike precision, meticulously striding in and out of frame even as the principal characters converse casually. It's a classic Luhrmann touch that does more for the film than nearly any of its dialogue.

Unfortunately, Luhrmann's sense of scene far outperforms his sense of pace. Too often, the director's splendid, dreamlike party sequences go on just a tad too long, and at the expense of key plot developments, tumbling past crucial moments of character-building more sloppily than Gatsby's gleeful, drunken guests. We get passing glimpses of the troubled, fearful Gatsby—a frown after a party, an uncharacteristic pause in conversation—only to lurch forward to another whimsical Sunday afternoon drive in Gatsby's Rolls Royce. It certainly keeps the proceedings lively, but it cheapens the emotional payoffs late in the film. By the time we reach the movie's pivotal final chapter, we've barely had time to blink, let alone pity Gatsby.

In a misguided effort to pay homage to the novel, Luhrmann inserts a few exact quotes from the 1925 book, literally stopping the film in its tracks and typing each letter on screen. Tobey proudly reads the lines, his lisp growing to a crescendo, the 3D text popping jubilantly from the screen. He knew that when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God. You'll appreciate Fitzgerald's famous prose all over again. You'll also wonder whether Luhrmann's bothered to read the book.

It's tough to say what might have saved this iteration of The Great Gatsby. Perhaps Luhrmann shouldn't have cast Tobey Maguire. Maybe he should have broken further from his source material, creating a film built entirely on spectacle instead of mixing classic prose with circus cinematography. Or maybe Luhrmann simply needs to admit he's not a novelist. The trouble is, he's trying so hard to be one.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed