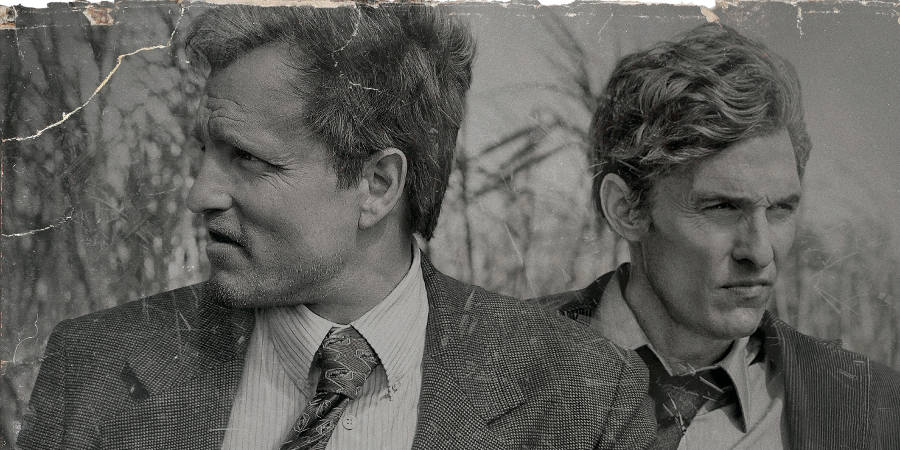

Then we meet our heroes. Rust Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) sits in a conference room, his eyes drooping, his hair long and unkempt, his posture signaling something halfway between boredom and defiance. We cut to Marty Hart (Woody Harrelson) dressed in a stiff suit and a suspicious grimace, answering questions carefully, nervously, uncomfortably. As we watch each man talk about his past, we feel the full weight of two decades, the detectives’ lives mysterious and misunderstood.

It’s a triumph of both style and character, a success True Detective milks—even as the plot and pacing falter—for each of its eight first season episodes. But behind the gloss are all the familiar beats of decades-old detection: two partners, one hard-boiled, one a little quirky; marital trouble; a lovable mistress; an auto mechanic who knows something; a dock worker who knows a bit more; a grumpy boss who tells the boys he’s thisclose to taking them off the case.

To be fair, there’s nothing wrong with perfecting the familiar formula. But True Detective doesn’t always stick to the formula, and that’s the problem. As the show slides from classic detective banter to Cohle’s meandering, philosophical monologues, you’ll sense the haze creeping in, a show caught between mystery and method, either unsure or unaware of its core. Are Cohle’s aloof observations critical to the narrative? Or are they just bits of bizarre babble meant to show that yes, in fact, Cohle is a complex, intriguing character? Either of the two on its own would have worked, but True Detective can’t seem to decide which way it wants to go.

The show stumbles, too, with its midseason clue-gathering, a journey that intrigues at the outset, but turns into a Carmen Sandiego hopscotch around town as we meet the Man at the Liquor Store who mentions the Old Woman in the Poor Neighborhood who recalls the Stock Character at Plot Development Café. By episode five, the actual detective work becomes less fun, with witnesses trotted out like cattle between the show's better, character-driven scenes.

It could have been much worse. True Detective might play whodunnit like it’s filling out an insurance form, but at least it plays fair. We get enough hints with enough time left to make some educated guesses, and you just might spot the villain a few episodes before our heroes do. Still, I longed for all the usual steps between the early clues and the final reveal. The best mysteries let us build the case, piece by piece, at roughly the same pace as our detective. We want to beat the man at his own job, but not by much. If we predict the case too soon, it wasn’t clever enough. If the detective’s solution seems too fanciful or too obscure, we’ll feel cheated. In True Detective, the problem isn’t so much that it strikes the wrong balance, but rather that it doesn’t care about this balance at all, with intricate riddles one moment, then formulaic interviews the next.

You could argue that I’m focusing on the wrong thing: True Detective sets a new benchmark with its mood, characters, and acting performances—just not with its plot. Given the show’s subject, however, I’m inclined to review the series the same way a detective would investigate a crime scene, looking for the fatal, hidden flaws—the sort of things that might be overlooked. The most famous killers aren’t remembered for their perfect crimes, but rather for their rare mistakes amidst a string of brilliant murders. I will remember True Detective’s first season for years to come, and how its stylistic flourishes almost fooled me. But hell: next to CSI and Law & Order, getting that close is something to celebrate.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed